This year’s Global Hunger Index looks at the links between hunger, how we produce and consume food, and the current Covid-19 pandemic, and argues that we must fundamentally change our food systems and adopt a One Heal approach.

2020: Laying bare the vulnerabilities of the world’s food system

The 15th report in the GHI series comes during a year that has seen the Covid-19 pandemic and the resulting economic downturn, as well as a massive outbreak of desert locusts in the Horn of Africa. These crises are exacerbating food and nutrition insecurity for millions of people, already shouldering the burden of hunger as a result of conflict, climate extremes and economic shocks.

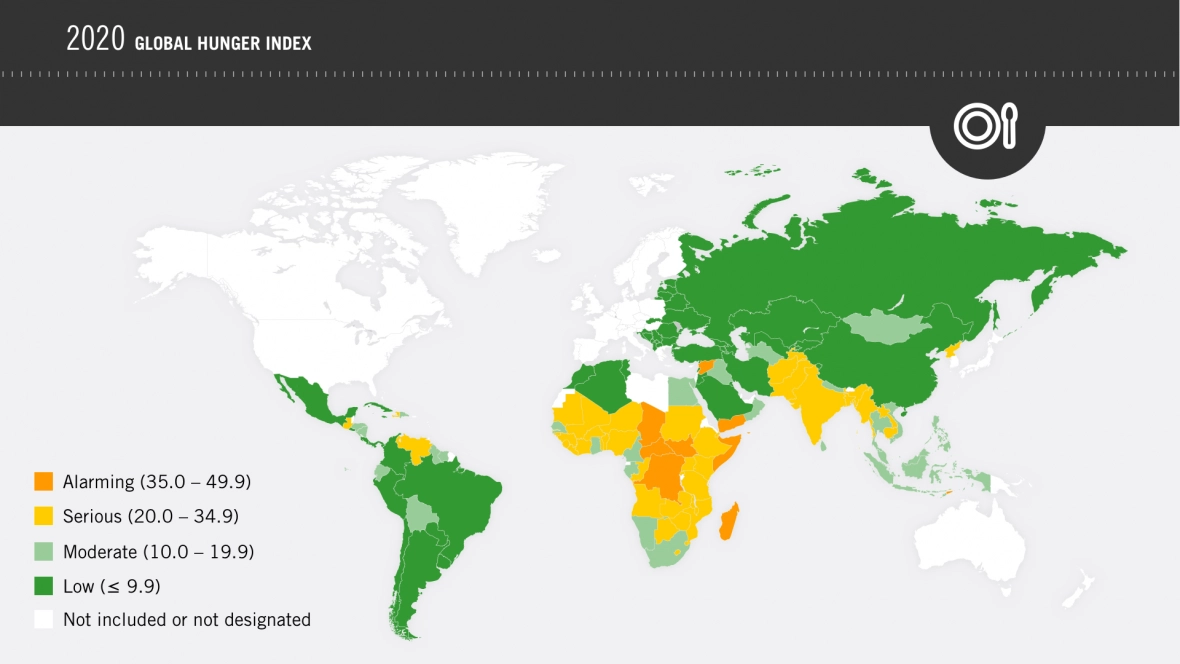

The 2020 GHI - which uses data from 107 countries to produce a ranking and categorization of hunger levels, ranging from ‘low’ to ‘extremely alarming’ - shows that, although hunger worldwide has gradually declined since 2000, in many places progress is too slow and hunger remains at a severe level.

The 2020 GHI scores are based on latest available official data which pre-dates the health, economic and environmental crises of 2020, and so the actual numbers of people suffering hunger today will be far more than is reflected in the underlying data.

That said, the GHI points very clearly to the hot spots where food insecurity and undernutrition are already severe – where populations are at greater risk of acute food crises and chronic hunger in the future.

How close are we to achieving Zero Hunger?

With 10 years left to achieve Zero Hunger, the 2020 GHI finds that the world is not on track to achieve this goal by the 2030 target. Although progress has been made, too many people are still suffering from hunger - and current crises are likely to worsen the situation for millions more.

Right now, nearly 690 million people are undernourished and 144 million children are suffering from stunting. In 2018 alone, 5.3 million children died before their fifth birthdays – in many cases as a result of undernutrition.

The report finds that ‘alarming’ levels of hunger have been identified in 11 countries including Chad; Burundi; Central African Republic; Democratic Republic of the Congo; Somalia; South Sudan; Syria, and Yemen.

In addition, hunger remains at ‘serious’ levels in another 40 countries.

The latest projections show that 37 countries will fail to achieve even ‘low’ hunger levels in the next decade, meaning the world faces an immense mountain if it is to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of ‘Zero Hunger’ by 2030.

Looking forward: A ‘One Health’ approach

The events of 2020 have shown that our food systems are unfair and inadequate in ways that are impossible to ignore. But, by taking an integrated approach to health and food and nutrition security, experts believe it may be possible to achieve Zero Hunger by 2030. A ‘One Health’ approach could help avert future health crises, restore a healthy planet and end hunger.

This approach is based on a recognition of the interconnections between humans, animals, plants and their shared environment, as well as the role of fair trade relations. It focusses on increasing sustainable practices in agriculture and improving the overall health of humans, animals and the environment – rethinking how we produce, process, distribute and consume our food, as well as reduce food loss and waste.

The 2020 GHI highlights the need to fundamentally reshape our food systems to be fair, healthy, resilient, and environmentally friendly – and a One Health approach could be transformative.

With only 10 years remaining until 2030—when the promise of Zero Hunger is due to be fulfilled—it is more urgent than ever to follow through on our commitment and actions to realize the right to adequate and nutritious food for all. The current crises must serve as a turning point not only to transform our food systems but to end the daily scourge of hunger - the greatest moral and ethical failure of our generation.