What We Do

Our work: Gender equality

We will only end poverty when we end gender inequality. Here’s how that works.

Read MoreCompiling data from Georgetown University's Women, Peace and Security Index and United Nations’ Gender Inequality Index, we look at ten of the worst countries for women’s rights where Concern is currently working.

Amid the ongoing #MeToo movement, debates around the gender pay gap and gender equality within the workplace (especially at the leadership level), women’s reproductive health and the so-called Pink Tax, it’s clear that gender has become a central lens through which we view our everyday lives, and a benchmark for us to measure the equity of our world.

We’re also faced with reminders of the gender inequalities that persist around the world, both the obvious — such as gender-based violence — and the more subtle norms and beliefs that fuel generations of imbalance. The Women, Peace and Security Index (copublished by Georgetown University and Oslo's Peace Research Institute) measures women's rights through levels of inclusion in society, representation in the justice system, and feelings of security (at home, in their community, and within conflict settings). The United Nations’ Gender Inequality Index touches on similar data points, such as the number of years of education a woman receives and women’s representation at the political level, as well as areas like maternal mortality, early marriage, and teen pregnancy.

Using these two sets of data, we’ve compiled ten of the worst countries for women’s rights. We also detail some of the issues unique to each context. Concern is working to address these issues through our work in each country.

There’s some debate between the 2021 WPS Index and the 2020 UN Gender Inequality Index as to Pakistan’s place when it comes to women’s rights. The latter ranks the country 135th out of 162. It's not a clean bill of health, but also not one of the top ten or even top 25 worst countries for women’s rights. But Women, Peace, and Society Index ranks Pakistan country as 167th out of 170, citing:

Part of the WPS's low ranking for Pakistan is due to the discrepancies between women’s rights at the province level. The lowest-ranking provinces in the country performed almost four times as poorly as the highest-ranking provinces. These are disparities that, the WPS says, “national averages conceal.” WPS links this to the income and poverty rates within provinces. They also link extreme poverty to gender inequality in Pakistan.

Conditions for women have improved somewhat in the Central African Republic, mainly thanks to a decrease in organized violence that improved a sense of community safety in the 2021 WPS Index. This is a drop in the bucket, however. A crisis in the Central African Republic has entered its tenth year in 2022 and has a disproportionate effect on women. According to the WPS:

In addition to the data that forms the heart of the WPS Index, there are other indicators of and barriers to women’s rights in CAR. Harmful gender practices like early marriage mean that 61% of married women were in a union before their 18th birthday. Women of reproductive age are also restricted in terms of their sexual and reproductive health and rights. According to UN Women, just over a quarter of Central African women were able to access modern family planning resources in 2019.

Somalia ranks twelfth on the 2021 WPS Index. Highlights from their report:

In some cases, the indicators to meeting the Sustainable Development Goal of gender equality in the country are incomplete, due in part to Somalia’s protracted cycle of crisis. There are worrisome gaps in reporting, including data on women’s land ownership rights, harassment and violence against women, and the gender pay gap.

Other indicators that the United Nations reports on do not suggest positive results in these areas. More than a third of Somali women were married before they turned 18. Only 2% of women in the country were able to access safe and modern family planning and birth control resources. This has led to one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world: For every 100,000 live births, 829 Somali women will die.

Even higher than Somalia’s maternal mortality rate is Sierra Leone, where 1,120 women out of every 100,000 will die due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth. This has been a longstanding issue — one that Concern has addressed in part through our project, Innovations for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (2009-2016). While many in the country are pushing to overturn outdated and outmoded gender norms, crises have interrupted progress, such as the 2014-16 Ebola epidemic leading to an increase in unplanned teen pregnancies.

While Sierra Leone has enjoyed relative peace for the last 20 years, gender-based violence is still a fact of life in many areas. According to the WPS Index:

The summer of 2019 brought several advances in women’s rights to Sudan, including:

This is a promising advancement for the country, though progress may be delayed given the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, only 22% of parliament was female-led (although this is already a huge step forward).

Of the 162 countries ranked on the United Nations’ Gender Inequality Index for 2020, Chad ranks 160. Chad passed its Reproductive Health Law 20 years ago, which has led to a significant decrease in practices like FGM. However, child marriage is still common — one report conducted by Concern in 2015 showed that the median age for a first marriage was 16 for girls and 22 for boys. In one focus group for this report, a participant noted: “Early marriage is a custom in our community, but a real danger for the girl: pregnancy, surgery, death, and also several cases of running away.”

“Early marriage is a custom in our community, but a real danger for the girl: pregnancy, surgery, death, and also several cases of running away.” — Concern Chad focus group participant, 2015

Since that report, we’ve seen numbers like the percentage of women reporting intimate partner violence drop. However there’s still a lot of work to be done:

The Democratic Republic of Congo ranks 163 out of 170 on the 2021 WPS Index and 150 out of 162 on the UN's 2020 Gender Inequality Index. Progress on gender equality in the DRC has been slow, with inequalities existing across all sectors. Many of these discrepancies exist at the legislative level. The WPS estimates 25% of national laws have some level of bias towards men. This has harsh ripple effects on gender equality in the DRC:

These numbers are reflected in the education discrepancy between genders: Men are almost twice as likely as women to go beyond primary education in the DRC — 65.8% of men versus 36.7% of women.

Harmful gender norms as a result of a patriarchal culture have left women in South Sudan excluded from decision-making and political activity. Women have few decision-making powers within the household. A lack of resource ownership and land rights is at the heart of power imbalances between the genders.

The 2021 WPS Index works with a bit more data on South Sudan, enough to rank it 165th out of 170 countries for women’s rights and security. A longstanding conflict in the country makes it less safe for women both in their communities and with their domestic partners — one in four South Sudanese women have reported intimate partner violence.

Before war broke out in 2011, gender dynamics in Syria were traditionally patriarchal: Women only gained the right to vote in national elections in the mid-1950s, and, while they were allowed to work, they made up a small percent of the pre-war workforce. Many Syrian women, particularly in the country’s then-thriving middle class, opted to stay at home and raise families. Syrians still view marriage as a contract between the husband and the wife’s father. It was only in 2020 that the country criminalized honor killings.

The protracted Syrian crisis has exacerbated many of these gender norms, while also introducing many of the gendered complications that come with conflict. One of the reasons Syria ranks so low on the WPS Index owes to ongoing conflict.

These numbers are even higher for Syrian refugee women. Syria performs slightly better on the UN’s Gender Inequality Index, however some of the determining factors — including years of education between men and women — are a bit skewed, as conflict has prevented an entire generation of Syrian girls and boys from having a basic education.

Afghanistan ranks last out of 170 countries on the WPS Index and 157th out of 162 on the UN Gender Inequality Index. More than four decades of conflict and crisis combined with regressive gender norms have left many Afghan women and girls uneducated.

Along with neighboring Pakistan, honor killings are illegal here, but still widely prevalent.

None of the issues listed in these countries, which rank among the worst for women’s rights, can be fixed overnight or through policy change alone. Change and progress towards gender equality happens at the community, family, and even individual level — questioning intrinsic gender norms held by and for both women and men, what it means to be a woman or a man, and how equity can coexist with tradition.

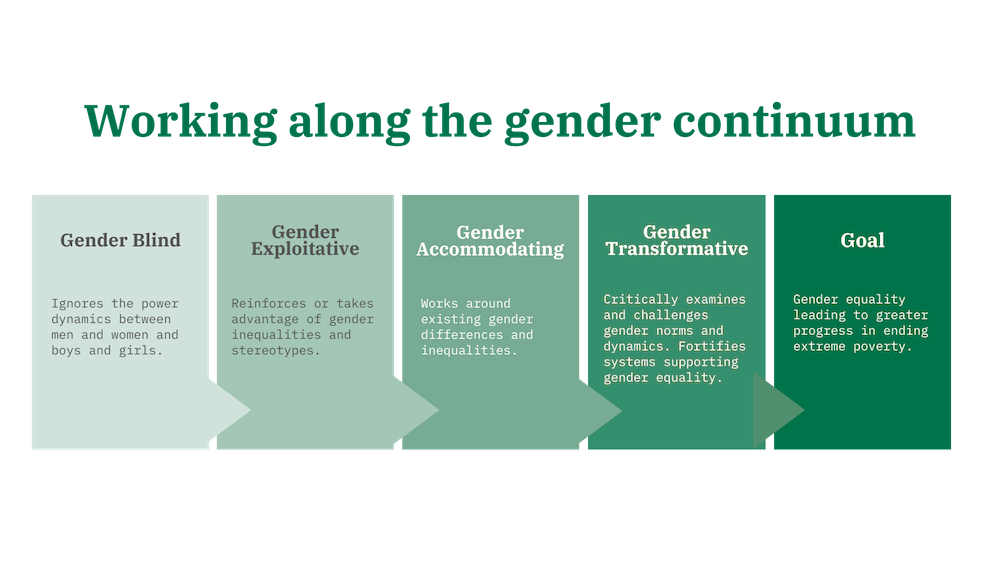

Yet we also see how deep the connections go between gender inequality and issues like poverty, hunger, conflict, and climate change. At Concern, gender transformation is at the heart of all of our programs, whether they’re designed to address agricultural challenges, help individuals build small businesses, respond to an acute crisis, or end hunger. As an international team of over 4,000, and with the millions of people we serve each year, critically examine and challenge gender dynamics in order to make greater, more sustainable progress towards ending extreme poverty. Where it makes sense, we also build and strengthen systems to support that level of equality.

These initiatives include mandatory gender training — for men and women — for participants in our Graduation program, a multi-year, multi-million Euro project to develop a safe learning model for schools in Sierra Leone, and advocating at the policy level with local and national representatives to ensure that new policies help to restore gender parity.