What We Do

Our Work: Health & nutrition

Ending global extreme poverty requires us to focus on two of its root issues: health & nutrition. You can help us with both.

Read MoreA drought in the Horn of Africa has left 7.1 million people in Somalia, 9.9 million people in Ethiopia, and 3.5 million people in Kenya facing varying levels of food insecurity. Somalia is at especially high risk for declaring famine before the end of the year. An ongoing and multifaceted crisis in South Sudan has 75% of the country’s population going to bed hungry each night. A similar crisis in Afghanistan has 40% of the population doing the same.

“Famine” is a word that gets used a lot in humanitarian contexts, but it has some pretty specific meanings. Here, we go into what a famine is, when it’s declared, how it’s measured, and the long-term impacts famine can have on individuals, communities, and countries.

Famines take place when a substantial percentage of a country’s (or region’s) population are unable to get sufficient food. This lack of food and nutrition security leads to high levels of acute malnutrition and death.

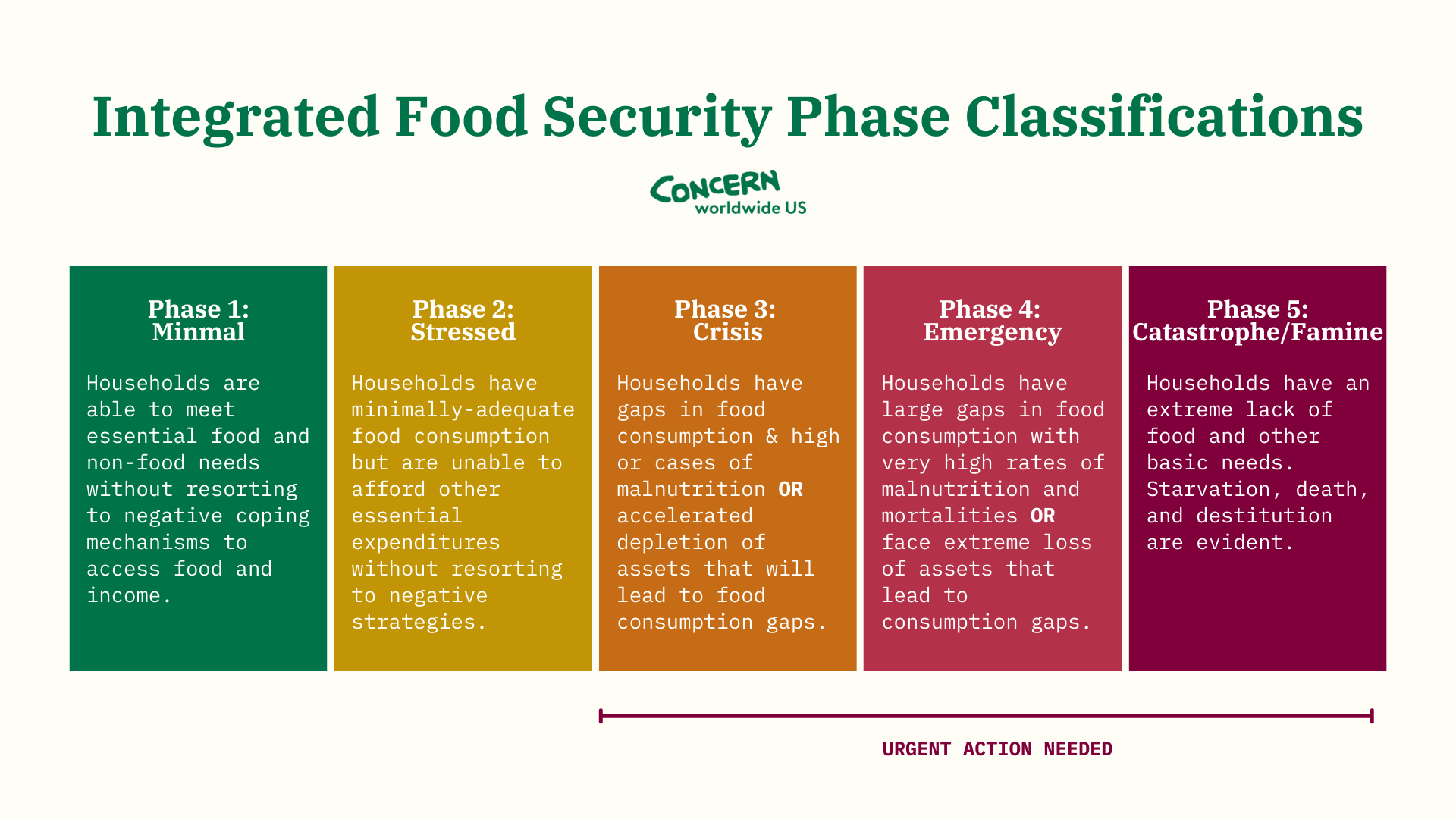

There are many countries with alarming levels of hunger and chronic food insecurity. This is why the United Nations designed the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC). The IPC measures a country’s food insecurity on a five-phase scale, from minimal food insecurity to catastrophic/famine-levels of hunger.

Famine (Phase 5 on the IPC) represents the highest levels of hunger and malnutrition in a region. A famine is declared when:

Famine can be declared across a country or either local or international regions. However, it’s up to individual governments to declare the beginning (and end) of a famine. This can be especially difficult in many of the world’s hungriest countries: Generally, famines occur in areas where there is a lack of infrastructure, which can make these data points hard to know for certain.

Many of the same causes of hunger also contribute to a famine. The World Food Programme points to five main causes of famine:

Looking at the above, you may notice that some of these causes are connected. These intersectionalities are one of the biggest reasons that a hunger crisis becomes a famine. In these situations, there is never an easy fix. The WFP also points out that these causes of famine (unlike some causes of hunger) are largely man-made, meaning that we can control the outcomes at a high-enough level. But this often requires international diplomacy, cooperation, and compromise.

Famine is more than just hunger. Its effects are further reaching, and last long after the famine is declared over.

The World Health Organization says: “Between starvation and death, there is nearly always disease.” Among the effects of hunger is a weakened immune system. Often, people who die during a famine don’t die from starvation, but from diseases that take advantage of their immune system’s vulnerability. These diseases can include cholera, malaria, measles, and tuberculosis. A pandemic like the coronavirus also profits off of compromised immune systems, especially among children, the elderly, and other people with comorbidities.

The health effects of famine can also carry on for generations, especially as malnutrition affects maternal and child health. Recent research conducted at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health in California shows another way that famine may impact health from one generation to the next:

“We have long known that exposure to nutritional stress and famine can lead to long-term health consequences including type 2 diabetes, schizophrenia, and hypertension, and that some of these effects may pass from generation to generation,” says lead researcher Qu Cheng, whose team focused on the intergenerational effects of the Great Chinese Famine (1959-61) and was the first to connect famine to intergenerational transmission of tuberculosis (TB). “We now know that more than 60 years later, this historic famine continues to exacerbate TB transmission as well, one of the world’s most intractable global infectious disease crises.”

“Between starvation and death, there is nearly always disease.” — The World Health Organization

Anyone who survives a famine may be at risk for chronic physical and mental health issues, among other residual effects. However, children are not only among the most vulnerable to mortality during a famine, but to a lifetime of impacts afterwards.

One of the main side effects for children suffering malnutrition is stunting (low height for age). Occurring early on in their childhood, stunting impacts body and brain development, often leaving children open to chronic health issues as well as lower IQ levels. This can have a serious knock-on effect: Studies have shown that children who are stunted are four times as likely to die than their non-stunted peers. If they survive to adulthood, they’re more likely to be caught in the cycle of poverty, earning 22% less than their peers.

Hunger and conflict go hand-in-hand. Not only is hunger one of the main reasons conflict breaks out, it’s also a means of continuing conflict once it erupts. There are instances of hunger being used as a weapon of war, and the more dire a food shortage is, the more desperate those living through it become. Tensions are exacerbated. Young men are more likely to join one side of the conflict in exchange for the promise of food and money. Women and girls are more vulnerable to harassment and violence.

Famine doesn’t happen overnight. With enough early warning and early action (EWEA), it can be prevented. We saw this happen in Somalia in 2017.

Traditional aid models, often by necessity, rely on certainty. But in emergency contexts, this doesn’t always work. As we saw with Somalia’s 2010-12 famine, waiting for the full picture of need and risk to develop wasted precious lead-time. Somalis paid the ultimate price. Breaking with tradition, we created an approach to emergencies called Early Warning, Early Action (EWEA). This “no regrets” strategy formed the foundation of our program Building Resilient Communities in Somalia (BRCiS).

Instead of responding to an emergency based on certainty, we began responding (proportionately) to the probability of a disaster. In some cases, this meant that we responded early to the signs of a crisis that didn’t come to pass. But, in the long term, EWEA still saves money: An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

As early as 2016, there were signs that the rains Somalis depend on for agriculture and pastoralism would fail the following year, putting millions of lives at risk. BRCiS team members began responding with monthly cash transfers to the most vulnerable households in the region. That November, as subsequent rains appeared to be failing, thereby increasing the possibility of catastrophe, we increased the amount of those cash transfers by 30% and doubled the number of families receiving these funds. We increased transfers once again in January of 2017, doubling the amount we initially paid families thanks to newly-accessed emergency funds from DFID and ECHO.

The rains failed, and crops along with them. However, markets continued to function and food remained available for purchase. No famine was declared in Somalia that year.

The majority of people Concern works with are involved in some way with farming and food production. Many of these communities are also on the frontlines of climate change. We work with rural communities to promote Climate Smart Agriculture, an approach that helps families adapt to better crops, growing techniques, and soil improvement practices in response to the changing — and often unpredictable — environment. We also work to strengthen links with the private sector to facilitate access to supplies and equipment.

We combine this with our award-winning and standard-setting program, Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM), which has saved millions of lives over the past 20 years. We’ve continued to work with partners and communities to find more tailored approaches to community-based treatment of childhood malnutrition, which has led to CMAM Surge: a way of proactively responding to malnutrition during seasonal “surge” periods throughout the year. Two CMAM Surge pilot tests in Kenya in 2012 saw that the model managed peaks, without undermining other health and nutrition efforts.

Supporting Concern means that $0.93 of every dollar donated goes to our life-saving work in 25 countries around the world. Last year, we were able to reach over 11.4 million people with our health and nutrition initiatives.