What We Do

Support Concern's Haiti Earthquake Response

100% of all donations will go directly to our current relief efforts following the August 14, 2021 earthquake.

Donate NowYou may have seen headlines about a worsening humanitarian situation in Haiti. And you most certainly saw headlines in 2021 following a political crisis and 7.2-magnitude earthquake. These moments have been just some of the latest inflection points in a country that has suffered more than five centuries of political instability—and the effects thereof. Here’s our at-a-glance guide to Haitian history.

Christopher Columbus lands on what is now known as Hispaniola (the island shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and claims it for Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. While this has been regarded as the beginning of Haiti’s written history, the island had been inhabited by indigenous Taíno (who referred to the land as Ayiti) since the BC era and had a rich history long before Spanish conquest.

In 1496, the first Spanish settlement on Hispaniola (and the first European settlement in the western hemisphere) is established in what is now present-day Dominican Republic. Five years later, after all but decimating the population of Taíno people, Spain brings 1,600 kidnapped and enslaved African people to the island to work in gold mines and on sugar plantations.

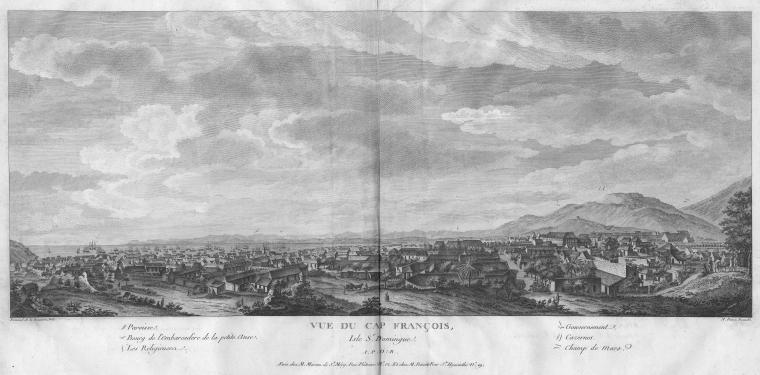

The first French settlers establish a colony on Tortuga Island and in the northwestern area of Haiti’s mainland, naming the territory Saint-Domingue. In the latter part of the 17th Century, under Louis XIV, France authorizes African slave trade in the territory and introduces the Code Noir, which not further restricts the rights of enslaved people — as well as the rights of free people of color — in all French territories .

In 1697, Spain cedes its territory in western Hispaniola to France. Under French rule, Saint-Domingue is the country’s richest colony in the 18th Century, producing half of all the sugar and coffee bought and sold in Europe and accounting for one-third of the Atlantic slave trade.

The 1789 French Revolution makes more people — on both sides of the Atlantic — outspoken for the rights of Black and indigenous people of color in the colony. France violently represses this activism, which leads to the beginning of the Haitian Revolution in 1791.

The Haitian Revolution continues for more than a decade, destroying much of Haiti’s agricultural resources and infrastructure. On December 4, 1803, French forces surrender to Jean-Jacques Dessalines in the northwestern commune of Gonaïves. For the first time in over 300 years, Haiti is once again an independent nation.

On January 1, 1804, Dessalines assumes the role of Governor-General. He declares himself Emperor later that year, and is assassinated two years later. This leads to a Haitian civil war between the north and south that lasts until 1820. Reunification following the second peace excludes Black Haitians from power.

Haiti's independence from France came at a cost: Reparations that cost the country approximately $20 billion that were paid through high-interest loans. The final payment was made in 1947.

French King Charles X agrees to formally recognize Haiti as an independent nation, provided that the country pay 150 million francs in reparations to France (approximately $21 billion in today’s currency, according to Forbes). Haiti takes out high-interest loans from American, German, and French banks to cover the cost (approximately 80% of the country’s annual national budget and 10 times its annual revenue).

In 1838, France reduces this debt from 150 million to 90 million francs (ca. $12.6 billion). The final payment on the double-debt of Haiti's reparations to France and its loans from the United States is made in 1947, nearly 150 years after independence.

After a series of border disputes with the Dominican Republic and short-lived presidencies culminating in the assassination of leader Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, the United States invades Haiti in 1915 to protect its investments in-country. The United States withdraws its forces in 1934.

Three years later, Dominican forces under the orders of President Rafael Trujillo kill an estimated 30,000 Haitians living in the border zone between the two countries in what’s known today as the Parsley Massacre.

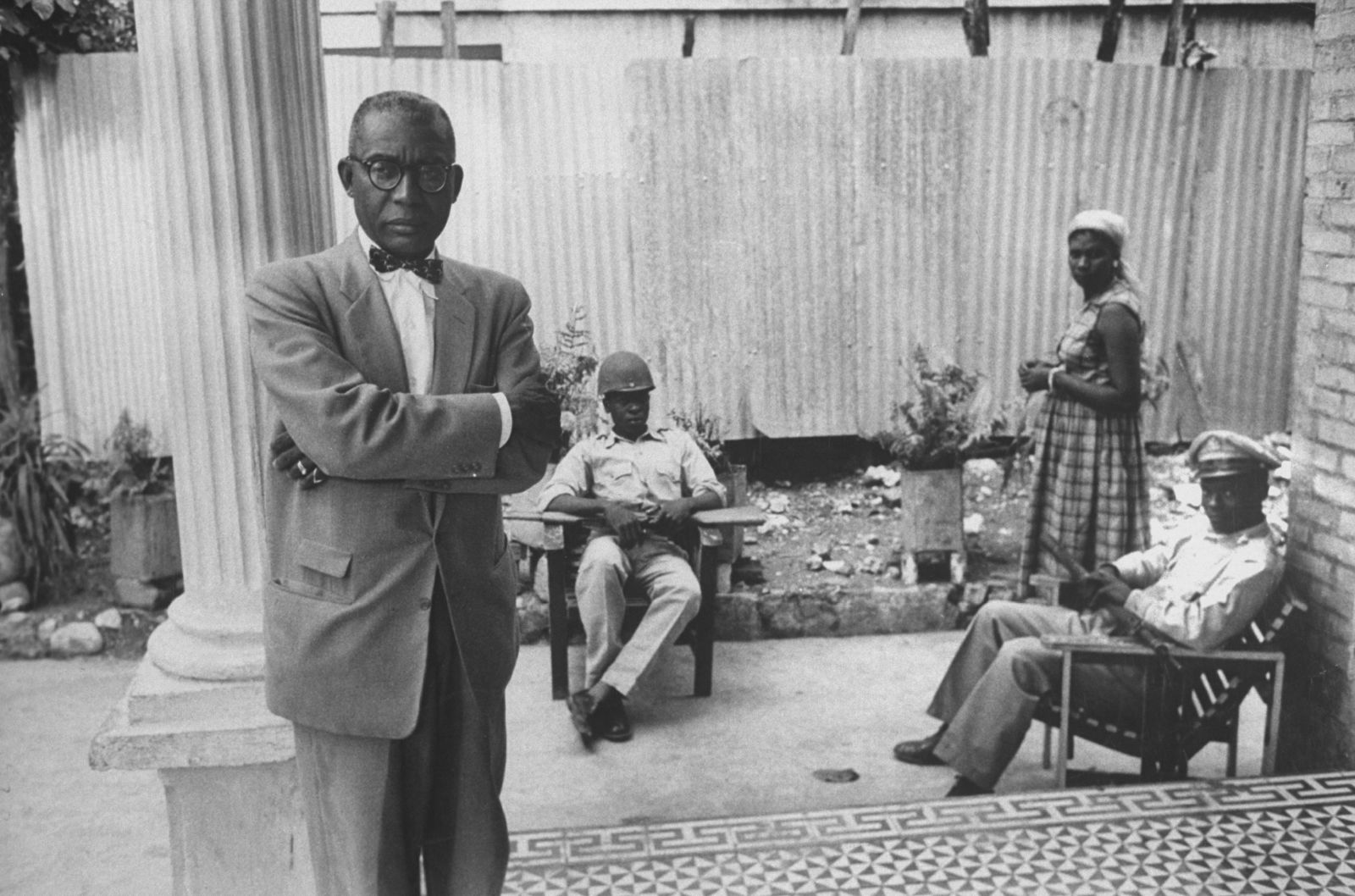

Shortly after Haiti celebrates 150 years of independence, Hurricane Hazel makes landfall in the country in October 1954, killing 1,000 and destroying coffee and cocoa crops at the beginning of harvest season. In 1957, following two failed elections, physician François “Papa Doc” Duvalier seizes power. His cult of personality turns despotic the following year when he establishes death squads to silence his opponents. In 1964, Duvalier declares himself president for life, a title he maintains until his death in 1971.

Following Duvalier’s death, his 19-year-old son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, assumes the title of president for life. A popular revolt in 1986, however, leads to Baby Doc fleeing Haiti. He is replaced by Lieutenant-General Henri Namphy.

The elections of 1987 are delayed following the assassinations of two candidates and a massacre of Haitian voters. Military-run elections in January 1988 declare Leslie Manigat the winner. He is overthrown in a military coup led by Namphy six months later. In September, Namphy himself is overthrown by General Prosper Avril.

Avril resigns amid protests. Former Salesian priest Jean-Bertrand Aristide wins the country’s first free and peaceful democratic elections, with a reported 67% of the popular vote. His rule is interrupted in 1991 by a coup led by former Brigadier-General Raoul Cedras. Aristide is exiled until Cedras himself gives up power and enters exile in September of that year.

Aristide returns to power in 1994. His reforms included increasing access to healthcare and education, including adult education and literacy, improving the country’s judicial system and civil rights, doubling the minimum wage, food distribution to those suffering hunger and food insecurity, livelihoods support and training, and dissolving the military.

After a presidential term by René Préval (1996-2000), Aristide is re-elected despite claims of fraud. Several failed attempts to overthrow Aristide’s government result in conflict across the country led by armed groups. Aristide is forced to resign in a 2004 coup and leaves for South Africa. A multinational UN Peacekeeping force returns to the country to maintain security and stability.

Floods damage parts of the country early in 2004, a vulnerability that is further exploited that September by Hurricane Ivan and Hurricane Jeanne. Jeanne kills at least 3,000 and leaves another 250,000 Haitians homeless. Flooding destroys key rice and fruit harvests.

Less than a year later, Hurricane Dennis kills 56 and causes an additional $50 million in damages for Haitians. 2008 sees a string of natural disasters within just one month, including Tropical Storms Fay and Hanna and Hurricanes Gustav and Ike, destroying 25% of the country’s economy.

On the afternoon of January 1, 2010, a 7.0-magnitude earthquake hits Port-au-Prince. The scale is unprecedented in an urban setting. While international donors pledge $5.3 billion to help Haiti rebuild, many fail to meet their commitments. Further issues with funds not making it to their intended uses continue to fuel popular dissatisfaction with leadership, especially when little progress has been made six months following the quake.

The country is further overwhelmed by a cholera outbreak — the first of its kind on record, and regarded by many to be the worst in recent history. Lasting for years, cases number 820,000 and approximately 10,000 are killed. After a violent election cycle, Michel Martelly wins the presidency. He designates Jovenel Moïse as his party’s candidate at the end of his term. Moïse wins two elections, held in 2015 and 2016, respectively, despite questions around their legitimacy, and takes office in 2017.

Hurricane Matthew makes landfall late in the season (October 4, 2016) and is the strongest storm to hit Haiti since 1964. In addition to destroying crops just before harvest time, it exacerbates the cholera epidemic, leaves 200,000 families without a home, and causes further damage to the country’s infrastructure. Haitian civilians, especially the most vulnerable, suffer these consequences the most, especially amid a lack of humanitarian funding. In 2019, the United Nations reports only meeting 30% of its funding goals for Haiti as many donors fall behind on financial commitments.

In March 2018, Venezuela stops its oil exports to Haiti, setting off a chain reaction of fuel shortages. That summer, the Haitian government halts fuel subsidies, which leads to price increases as high as 50%. Protests begin and continue into 2019, often with violent, at times deadly clashes between demonstrators and police. By the summer of 2019, the country goes on lockdown, which lasts for two-and-a-half months and blocks access for many humanitarian organizations into especially-vulnerable communities.

COVID-19 lockdowns add to income loss and food insecurity and increasing civic unrest. Political insecurity also continues, with a constitutional crisis provoked over President Moïse’s term limit and refusal to leave office before 2022. Moïse is assassinated in his own home in July, 2021. Ariel Henry is confirmed as prime minister, and also takes on the role of acting president.

Five weeks after Moïse’s assassination, a 7.2-magnitude earthquake hits western Haiti, approximately 55 miles north of Les Cayes. It is the largest natural disaster to hit the country since the 2010 earthquake.

Gang violence takes over with separate major clashes in April-May in the southeastern Plain of the Cul-de-Sac region, and in July in the capital of Port-au-Prince. UN Special Representative Helen La Lime sums up the impact this has, in tandem with other recent developments: “An economic crisis, a gang crisis, and a political crisis have converged into a humanitarian catastrophe.”

Conditions continue to deteriorate in 2023 with increased reports of homicides, rapes, and kidnappings. On July 27, the United States orders all non-essential personnel to leave the country. By September, reports confirm that 80% of Port-au-Prince is under gang control. Kenya agrees to lead a “multinational peace mission,” which is approved by the United Nations in October as a “multinational security support mission” (Resolution 2699). The UN reports that, in 2023, there were 2,490 kidnappings and 4,789 homicides.

Despite the UN’s approval of Resolution 2699, and further commitments from the United States, Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Bangladesh, Benin, Chad, and Jamaica, the mission has yet to launch on the ground.

Following pressure from former senator Guy Philippe and an armed following, Ariel Henry announces his resignation as president on March 11. The Kenyan government suspends deployment to Haiti until a new government is formed. A deal for a temporary government, which would last until February 2026, is proposed on April 7.

Meanwhile, escalations in violence continue to threaten civilians around the country. In the first quarter of 2023, the UN reports 1,554 deaths and 826 injuries due to violence.

Concern has been in Haiti since 1994, when we responded to Hurricane Gordon. Over the course of 30 years, we have responded to every major emergency in the country, including the 2010 and 2021 earthquakes, Hurricane Tomas (2010), and Hurricane Matthew (2016).

In early 2024, we escalated our emergency response in Haiti to meet the increasing needs, thanks in part to a $2.1 million grant from USAID to assist over 32,800 people affected by the country’s hunger crisis. This assistance includes electronic vouchers that help families purchase from local vendors. We are also working with local authorities and communities to prevent and mitigate the spread of cholera through waste removal, handwashing stations, and hygiene kit distribution. In collaboration with our local partners, Concern has also improved access to services, including psychosocial support, for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence. In 2023, we provided care to 3,077 people.

Despite the prevalence of violence, Concern Haiti’s Kwanli Kladstrup believes that peace is achievable — and necessary: “Prevention of future violence, and sustained support for the most vulnerable — especially children — should be our guiding principles to ensure the next generation does not pursue violence as its only option. The potentially violent actors of tomorrow are the children of today. Therefore, it is most important that their rights to education, good health, and protection are fulfilled; and right now that is just not happening.”