News

The Haiti crisis, explained: What you need to know in 2024

Learn more about the last six years of the humanitarian crisis that have unfolded in Haiti.

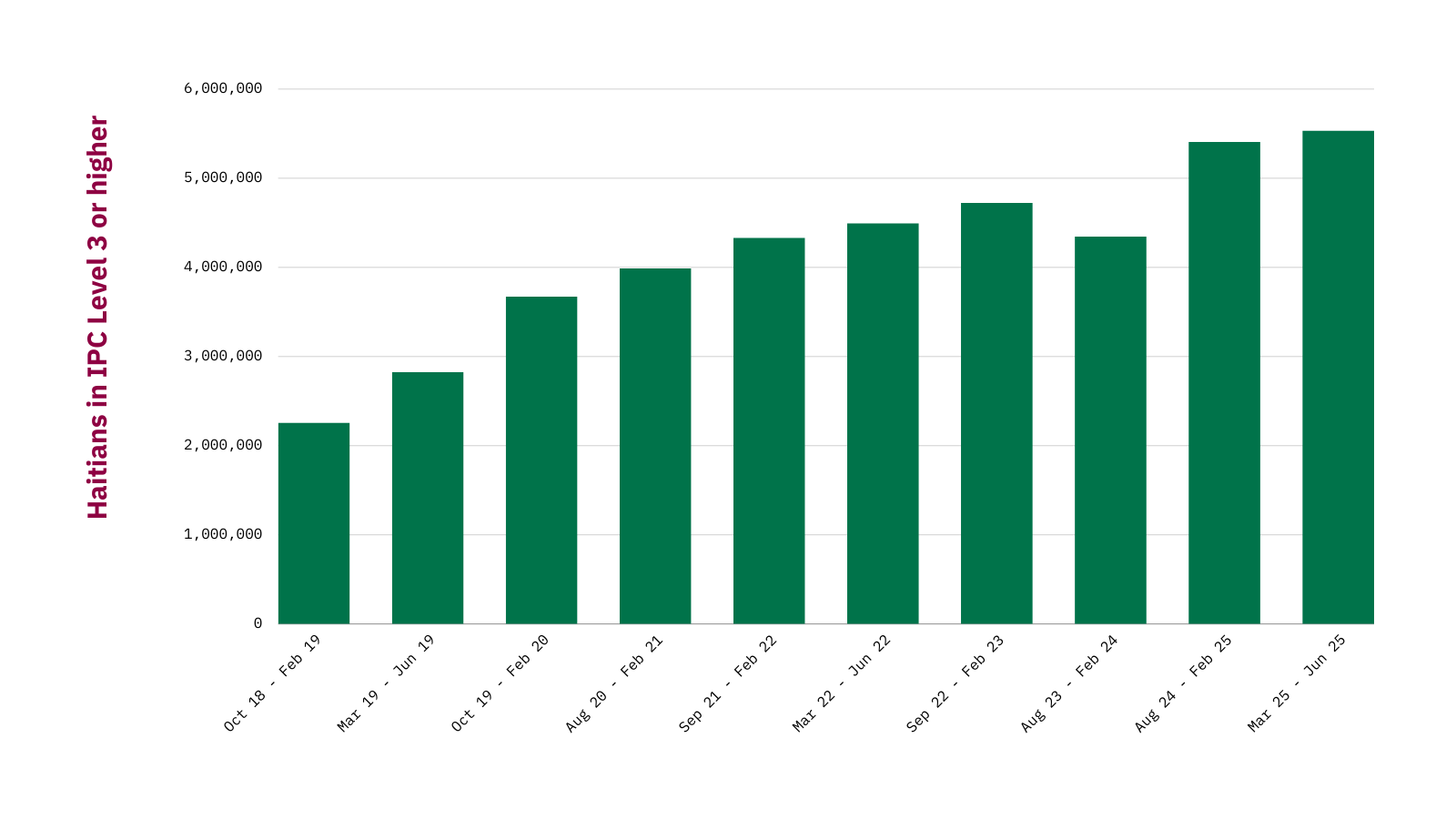

Read MoreAt the end of September, Haiti marked a grim milestone when the latest Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) reported that one in every two Haitians was facing acute hunger. That amounts to approximately 5.4 million Haitians struggling to feed themselves and their families each day, including nearly 6,000 facing famine-like conditions.

Since then, the situation has continued to grow dire: Last month, the prime minister of the country’s transitional presidential council was removed from office, leading to a surge in violence throughout the Caribbean nation, which Concern and Welthungerhilfe ranked as the sixth hungriest country in the world on the 2024 Global Hunger Index. In just a few weeks, 40,000 people have been newly-displaced due to the unrest. Given this, the IPC expects to see hunger levels continue to rise in the first half of 2025.

Food insecurity has been a fact of life in Haiti for decades. However, hunger rates have increased dramatically over the last five years in tandem with the intensification of Haiti’s humanitarian crisis.

At the beginning of 2019, the IPC estimated that 2.25 million Haitians were facing acute food insecurity (placing at IPC Phase 3 or higher). As we close out 2024, that total is now up to 5.40 million, representing a 139.4% increase in the last five years.

The severity of hunger levels has also increased. At the beginning of 2019, approximately 82% of people dealing with acute food insecurity were at IPC Level 3 — a crisis level of hunger, but still a few grades off from an emergency (IPC Phase 4) or famine (IPC Phase 5). By the end of 2022, the 2.891 million Haitians at IPC Level 3 represented just 60% of those facing acute hunger, and that total included nearly 20,000 facing famine-like conditions. Likewise, the number of Haitians at IPC Level 4 rose from 386,000 in 2018 to just over 2 million in 2024 — an over 400% increase in emergency levels of hunger.

“Haitians are facing crisis after crisis, with no chance to recover or lead a normal and peaceful life,” says Concern Haiti Country Director Kwanli Kladstrup. “What we are witnessing is a full-blown security, protection, and hunger crisis.”

While the current hunger crisis didn’t begin in 2019, we can pinpoint this as a time when conditions took a major turn for the worse. That summer, following deadly clashes between protestors and police over fuel prices, the country went into a ten-week lockdown that restricted access for humanitarian organizations. This set off a chain of events that further eroded the country’s political security (as well as financial and food security) that came to a head in 2021 with the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse and, five weeks later, a massive 7.2-magnitude earthquake.

“What we are witnessing is a full-blown security, protection, and hunger crisis.” — Kwanli Kladstrup, Country Director, Concern Haiti

In the wake of this, gang violence took over the country. By September 2023, reports confirmed that 80% of the capital of Port-au-Prince was under gang control. These conditions have continued to worsen throughout 2024, and civilians are feeling the cumulative impact of the last five years. “While markets may still have food, violence and security mean that people in Haiti can neither access it nor afford it,” adds Kladstrup.

One of the main challenges that Haitians are facing at the moment when it comes to getting enough food is displacement. The World Food Program reported earlier this month that the number of internally-displaced people in Haiti has exceeded 700,000, mostly in Port-au-Prince and the Artibonite region. Roughly 50% of these people are children, and this figure represents a 22% surge in just the last three months — a mass exodus that makes getting food increasingly difficult.

The UN’s International Organization for Migration notes that approximately 83% of displaced people are sheltering with families, which has placed additional strain on coping mechanisms for households that have limited financial and social safety nets and more mouths to feed. Inflation has been especially volatile in the last few years, with the World Bank recording an 18.7% inflation rate on consumer goods in 2019 that shot up to 36.8% in 2023.

While this crisis has been a long time in the making, it hasn’t been the norm for Haiti, a country originally colonized for its fertile land and abundant resources. Until roughly 40 years ago, the country’s main crop, particularly in the country’s breadbasket of the Artibonite Valley, was rice. However, in 1984 the United States enacted the Caribbean Basin Initiative, a trade initiative that imposed both tariff and trade benefits to several countries in the area.

In the case of Haiti, which at that point was facing another period of political instability, the CBI was disastrous. In an effort to accelerate the country’s economy, it re-allocated nearly one-third of food production towards exports, dramatically reducing rice production and leaving Haitians reliant on imported rice from the United States.

“Today, the price of locally-grown rice in Haiti is two to three times higher than imported rice. It makes no sense.”

If you’re currently revisiting the history of tariffs in the US, the CBI also shrank tariffs on rice imports in Haiti from 35% to 3%, to the benefit of American rice farmers and detriment of their Haitian counterparts. “Today, the price of locally-grown rice in Haiti is two to three times higher than imported rice,” Victoria Jean Louis, former program director for Concern Haiti, said in 2022.. “It makes no sense.”

For Haitian farmers, a lack of credit options or subsidies despite this shift in priorities decreased productivity. Today, three decades since the CBI, they’re still behind in terms of having financial or technological resources to improve harvests (especially in the face of climate change). Meanwhile, Haiti now relies on imports for 80% of its rice, as well as 100% of its cooking oil and roughly 50% of other food staples.

The human cost of this food crisis has left many Haitians faced with solutions that are desperate. One of the most common things Haitians have been eating isn’t even strictly food. Bonbon tè, also known as galettes, are cookies made from dirt that sell for roughly $0.05 in many street markets. Traditionally, these galettes are made from dirt specifically from a plateau near the central town of Hinche, which is mixed with salt, fat, and water and baked in the sun.

They’re especially popular with pregnant women and young children due to the dirt’s high calcium content (which have also led their popularity as an antacid). However, their main ingredient is still dirt, which carries several health risks. “Trust me, if I see someone eating those cookies, I will discourage it,” Dr. Gabriel Thimothée, who was recently reappointed as Director General of Haiti’s Ministry of Public Health, told NBC.

In recent years, hunger in Haiti has led to many impossible decisions. In 2021, then-24-year-old Cité Soleil resident and peace activist Duval Dormeus told Concern that hunger has led to many young people joining in the violence as a means of feeding themselves and their families. “My mother always told me that if you are hungry in your belly, you can’t do anything else,” Dormeus says. “What else can you do but join an armed group?”

Concern has been in Haiti since 1994, when we responded to Hurricane Gordon. Over the course of 30 years, we have responded to every major emergency in the country, including the 2010 and 2021 earthquakes, Hurricane Tomas (2010), and Hurricane Matthew (2016).

In early 2024, we escalated our emergency response in Haiti to meet the increasing needs, thanks in part to a $2.1 million grant from USAID to assist over 32,800 people affected by the country’s hunger crisis. This assistance includes electronic vouchers that help families purchase from local vendors. We are also working with local authorities and communities to prevent and mitigate the spread of cholera through waste removal, handwashing stations, and hygiene kit distribution. In collaboration with our local partners, Concern has also improved access to services, including psychosocial support, for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence. In 2023, we provided care to 3,077 people.

Despite the prevalence of violence, Concern Haiti’s Kwanli Kladstrup believes that peace is achievable — and necessary: “Prevention of future violence, and sustained support for the most vulnerable — especially children — should be our guiding principles to ensure the next generation does not pursue violence as its only option. The potentially violent actors of tomorrow are the children of today. Therefore, it is most important that their rights to education, good health, and protection are fulfilled; and right now that is just not happening.”