One of the main causes of hunger is conflict which, especially when drawn out over years or decades, can lead to significant consequences for civilians trapped in combat zones.

Sometimes this is collateral damage, with hunger and even famine resulting from collapsed infrastructures, forced displacement, and regional closures. Sometimes, forces have more deliberately used hunger as a weapon of war. Historically, we’ve seen both examples at Concern, beginning with our emergency response to the Biafran Famine.

Since that initial response over 50 years ago, we’ve seen how prolonged conflicts and systematic military strategies both create the conditions necessary to declare a famine: At least one in five households face an extreme lack of food, more than 30% of children under the age of 5 suffer from acute malnutrition, and deaths exceed two out of every 10,000 people per day. Here’s how those conditions have played out over five decades and in 13 famines.

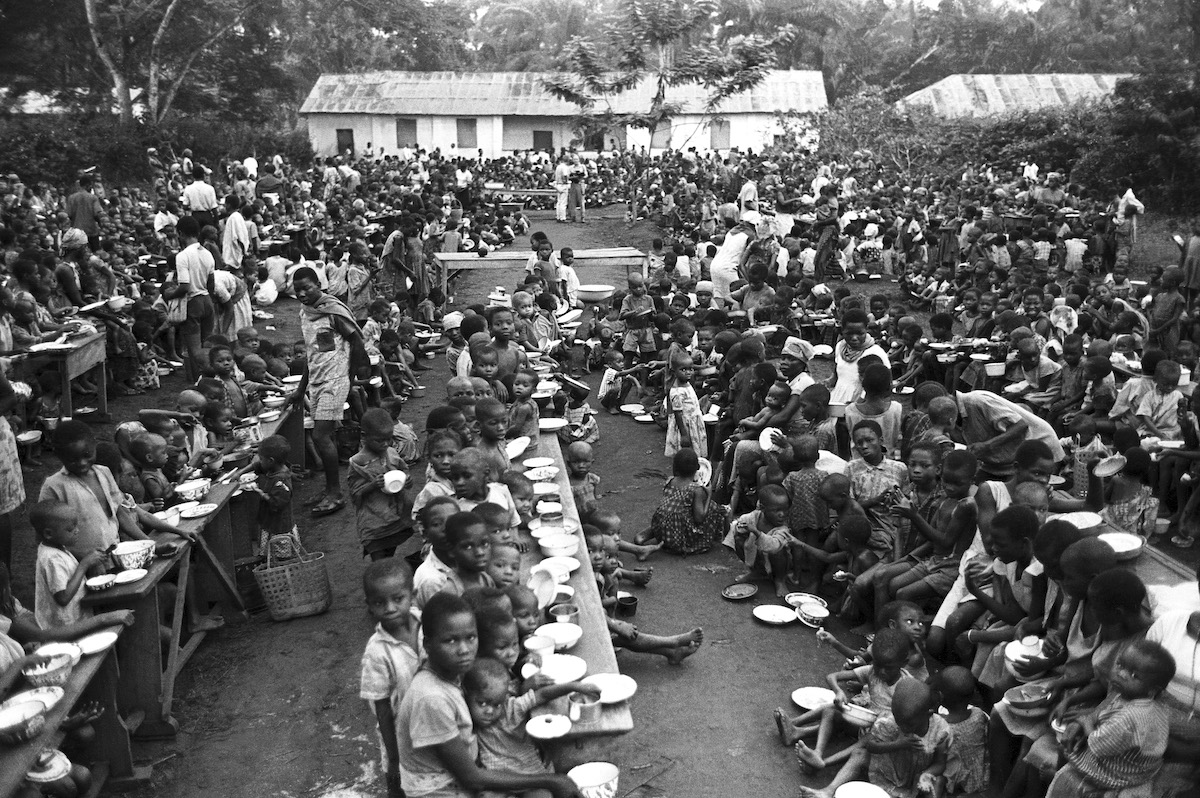

1967-70: The Biafran famine

Nigeria gained sovereignty from the United Kingdom in 1960. On 30 May 1967, the country’s eastern territory of Biafra declared its own independence. Since Biafra’s oil reserves were key to the economy, Nigerian authorities opposed the secession. By June, Nigerian troops advanced, put roadblocks in place, and declared starvation as a legitimate weapon of war.

Food was cut off from the 13 million inhabitants of Biafra. Hunger first took hold in the region in September of 1967, and for three years Biafrans were deliberately starved to death. At the height of the war, an estimated 10,000 people (including 6,000 children) died from starvation every day. In three years, an estimated 2 million civilians, or 15% of Biafra’s population, died.

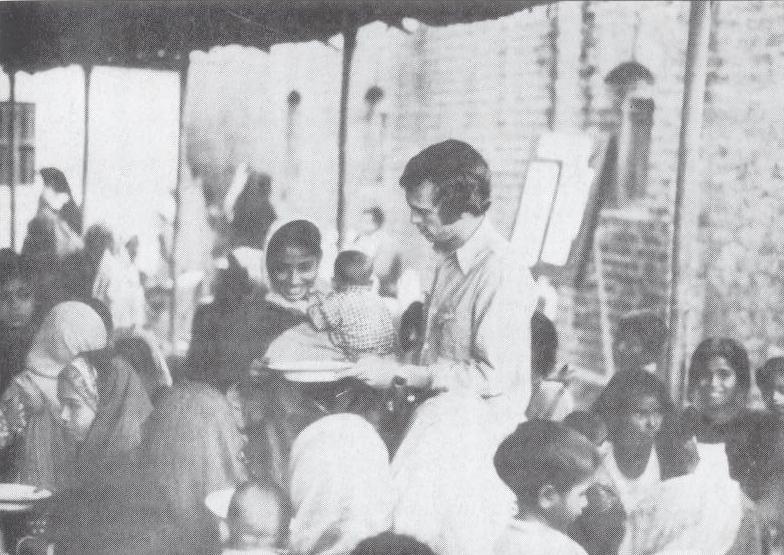

1974: Bangladesh

In some cases, hunger isn’t a weapon of war. Rather, it’s a consequence thereof. After nine months of conflict, Bangladesh gained independence from Pakistan in 1971. But the years following peace were no less tumultuous. As studies of conflict and hunger have shown, the effects of violence can affect communities for years after peace is declared.

Bangladesh suffered high inflation rates following the war, a result of the destruction of its infrastructure and economy. By early 1974, rice prices rose dramatically, a spike that continued through that summer. At the same time, floods destroyed crops, causing even greater shortages and inflation. Foreign aid reached Bangladesh late in the year. By then, estimates of fatalities related to this famine range between 27,000 and 1.5 million.

1975-79: The Khmer Rouge famine

The Cambodian Civil War claimed an estimated 25-33% of the country’s pre-war population. Many of these deaths were attributed to the Khmer Rouge’s labor camps, where malnutrition (among other issues) was rampant. But the regime’s weaponization of hunger extended past these camps. As one World Food Program official told Time Magazine in 1979: “I can tell you after what I have seen I am willing to kill myself to get food for these people.”

Along with UNICEF and the International Red Cross, the WFP struggled to get emergency food rations into Cambodia. However, they fell well short of the minimum 635 tonnes of food needed each day, often blocked from accessing the designated areas. This was deliberate on the Khmer Rouge’s part, who knew that by weakening opposition forces they would be unable to fight. During the Cambodian genocide, an estimated 500,000 people died due to famine alone.

1980-81: The Karamoja famine

In 1979, Ugandan president Idi Amin was overthrown as part of an eight-month war fought with Tanzania. The instability left in the wake of this shift in power combined with a drought to create one of the worst famines based on mortality rate. In the country’s northeast, 21% of the population was killed.

The Washington Post reported in 1980: “Veteran relief officials acknowledge that there have been worse droughts. But they say they have never dealt with a famine situation where there are so many additional problems and where such a high percentage of a small population is threatened with extinction.”

1982-85: The Mozambican Civil War

A 16-year civil war in Mozambique resulted in 1 million civilian casualties and, in the 1980s, two major famines. While a 1992 Human Rights Watch report doesn’t directly name hunger as a weapon of war used by either of the main factions, it does correlate “the combination of military strategies and human rights violations” with a famine that “cost many more lives than [had] been lost directly on account of the violence itself.”

1984-98: The Second Sudanese Civil War

Four famines took hold of Sudan as a result from the country’s Second Civil War, which began in 1983. The initial famine was declared on November 29, 1984 and lasted into 1985. It also contributed to the country’s political instability, as former president Jaafar Nimeiri failed to provide relief when the country was hit with a drought. As Alex de Waal wrote in his essay for the 2015 Global Hunger Index, “a government that cannot feed its people has forfeited its legitimacy.”

An estimated 250,000 Sudanese died in the initial famine, followed by another 250,000 in a 1988 famine in Bahr El Ghazal (now part of South Sudan). An Africa Watch Committee report cited by de Waal describes this famine as “an entirely man-made disaster.” Government and rebel forces “used military tactics that had the foreseeable consequence of creating famine, including the systematic denial of food relief.” Human Rights Watch attributed similar circumstances to the 1998 famine in the same region, one that killed an additional 70,000. In between, a famine in 1993 in present-day central South Sudan killed 20,000. The geography of these locations formed what was described at the time as a “famine triangle,” one that is still felt in South Sudan to this day.

1991-92: The Somali Civil War

The collapse of Somalia’s central government in 1991 marked the decline of the country’s infrastructure. That same year, a drought took hold of the Horn of Africa. With agricultural resources limited and an absence of government oversight, violent factions weaponized what food was available to exert control, burning crops in the country’s main agricultural regions and causing many Somalis to flee their homes in favor of displacement.

Food insecurity persists in Somalia today, with another major famine attributed to drought (and one narrowly averted in 2017). It was ranked as the hungriest country in the world for 2021, and more than 50% of its population of 10 million faces some form of food insecurity. Conflict continues to cut off access to certain regions, which prevents food and other goods from moving from one part of the country to another. “It’s breaking down the food system, basically,” explains Amina Abdulla, Concern’s Regional Director for the Horn of Africa. “It has made food inaccessible due to the high prices of basic food commodities… [and] affects how the population engages with the market. The uncertainty that conflict brings is a disincentive for people to produce food.”

2003-05: The war in Darfur

As the Second Sudanese Civil War began to wind down in the early 2000s, another conflict sprang up in its wake in the western region of Darfur. In 2003, various rebel groups attacked government police stations to highlight the economic and social isolation of the region. Already stretched thin by two decades of civil war, the government mounted a counter-insurgency strategy and supplied arms and weapons to various militia groups to fight the rebels. The result was massive displacement of the civilian population to camps as people fled for their lives. The violence and displacement also pushed a tenuous food security situation over the edge, resulting in famine returning to the region. Estimates place the mortality rate at around 180,000 due to hunger and related disease.

2017-18: South Sudan

Famine has been part and parcel of South Sudan’s history, as we saw above with the Second Sudanese Civil War. Amina Abdulla characterizes the now-independent republic as “one of those countries where you see an interplay between conflict and climate change and their impact on food security.” Yet, even with the climate crisis, the land still has potential, which means conflict is by no means a secondary factor.

“It has the most fertile land, which could be a bread basket for the region,” says Abdulla. “You’ve got two main rivers that flow through the country and potential that has never been realized as a result of conflict throughout the decades.” But in the last five years, political instability has increased in the country. Famine was declared in parts of the Unity State in 2017. At the end of 2020, an IPC survey classified 6.3 million people as living with severe food insecurity, 105,000 of whom were facing “catastrophic” levels of hunger.

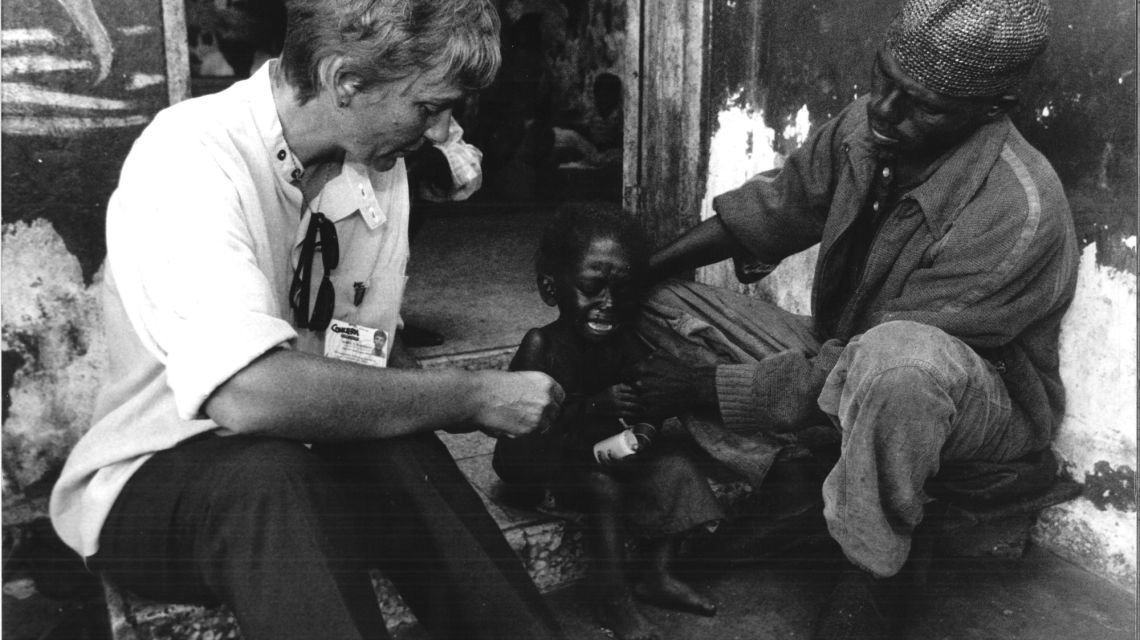

Concern’s work to end hunger

From Afghanistan to Yemen, Concern’s Health and Nutrition programs are designed to address the specific, intersectional causes of hunger and malnutrition in each specific context. Our projects often combine two or more of the following areas of focus: agriculture and climate response, maternal and child health, education, livelihoods, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH).

We played a key role in developing Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM), which has been recognized by the World Food Program as the gold standard for treating malnutrition. Other recent successes, like Lifesaving Education and Assistance to Farmers (LEAF) have seen entire communities not needing humanitarian food aid for the first time in decades due to holistic and systemic shifts in agricultural practices and community care.

Last year alone, Concern reached 9 million people with health and nutrition programs in 21 countries. Your support can help us to do even more in the year ahead.