The cycle of poverty — and how we break it, explained

How Concern understands extreme poverty, and how that informs our work to end it.

Read MoreIn 2022, the gender pay gap remains an issue for every single country in the world — especially nations with higher rates of poverty.

The Equal Pay Act, signed into law by John F. Kennedy in 1963, was created in response to a long campaign of protest and agitation against unequal pay in the United States. In a way though, it was just the beginning of an even more complex debate. Arguments over appropriate data and the root causes of continuing pay inequity continue to this day, but one fact is indisputable: In 2021, the gender pay gap remains an issue for every single country in the world. It especially affects nations with higher rates of poverty, and is one of the barriers to ending extreme poverty.

In this guide, we go over some of the most common gender pay gap myths, while offering up some concrete facts, and adding some suggestions on what needs to happen to ensure real progress towards gender equality — in salaries and beyond.

You may have heard the popular claim that women in the American workplace make $0.78 for every dollar that their male counterparts earn. A survey from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) confirmed that number as recently as 2015, and comprised data from 3.5 million American families collected between 2009 and 2013. Yet this gap can increase or decrease based on specific details.

While the $0.78 figure doesn’t tell the whole story, it still doesn’t mean that the entire concept is flawed. For instance, a CNN investigation of the BLS study revealed that, among elementary and middle school teachers surveyed, women held more than 70% of the jobs but only earned around $0.87 to the dollar compared to their male counterparts.

Some of the statistics may be misleading, outdated, or just plain wrong — but using these errors to discredit the existence of the gender pay gap is also misleading.

As mentioned above, some of the statistics quoted around the gender pay gap are misleading (and in some cases, outdated or just plain inaccurate). However, using these errors as an excuse to discredit the idea of gender disparity in pay is also misleading.

The World Economic Forum (WEF), which publishes an annual report on gender equality across sectors, not only considers the actual dollar figures earned by men versus women, but the gap between these salaries based on similar roles. The WEF’s latest report shows a median income gap of 13.5% to 15%. Some UN estimates go as high as 30%.

The $0.78 gap applies, broadly, to white American women. However Black and Latina women in the United States make even less ($0.64 and $0.56, respectively, for every dollar). Outside the US,, the gap is wider still. The World Economic Forum’s global average suggests that women only earn $0.54 on the dollar. Other data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development suggest that a woman’s salary drops by 7% for every child she has, as well as evidence that the inverse is true for men: A father’s salary increases for every child he has.

Through Concern’s work with inequality and marginalization, we know that race and ethnic heritage are not the only ways that women lose out. These inequalities are often intersectional, especially when it comes to earning potential. Factors like the number of children they have can keep many women further from the best-case wage gap. Women in sub-Saharan Africa without children, for instance, only make 4% less than their male counterparts. Women with children? 31% less.

True, women are more likely than men to have lower-paying jobs, but this is also a nuanced statistic. Women are more limited than men in terms of livelihood options due to gender discrimination (especially in STEM fields such as science, technology, engineering, and mathematics — subjects that women perform well in at school but tend not to follow as careers). Sexual harassment and gendered violence also keep women out of certain workplaces and even whole industries.

In countries that rely on agriculture and pastoralism for employment, women are hindered by traditions around land rights. In the words of our activist friend Bono, “They can work the land, but they can’t [expletive] OWN the land.” Also, female farmers often lack access to the same tools, seeds, and other resources as their male colleagues, meaning that their land is less productive.

Many women have no choice but to take a lower-paying job for fewer hours because of the “invisible” labor expected at home: cooking, cleaning, raising children, and being a caretaker to other family members are generally unpaid and undervalued roles that women are more likely to play in a family due to longstanding gender norms.

However, WEF data show that women work just as many hours — if not more — than men. The problem is that much of their invisible labor goes unpaid, and unrecognized as essential work. Going by WEF data, men work an average of 7 hours per day, with 6 of those working hours being paid. Conversely, women work approximately 7.5 hours per day, with just 3 of those working hours compensated.

Key to changing this situation is recognizing maternal and paternal care as paid, necessary absence from the formal workplace, and for men and women to more evenly split the unpaid hours that go into parenting and running a household.

As we mentioned above, the pay gap is one aspect of gender inequality, but there are also pay gaps based on other inequalities and ways in which communities are marginalized. The cycle of poverty is fueled by these inequalities. Closing the wage gap is only one action that must happen in order to finally establish parity and end poverty.

In some countries, progress towards gender pay parity is actually stalling, according to the WEF’s latest report. There is currently no country in the world that has achieved full gender wage parity, even those with the highest marks otherwise in the quest for equity.

Year over year, almost 68% of the countries surveyed by WEF have done much to improve their progress, but this work is multifaceted and there’s still a lot to be done. Some of the main steps that can help to achieve equal pay for an equal quality of work include:

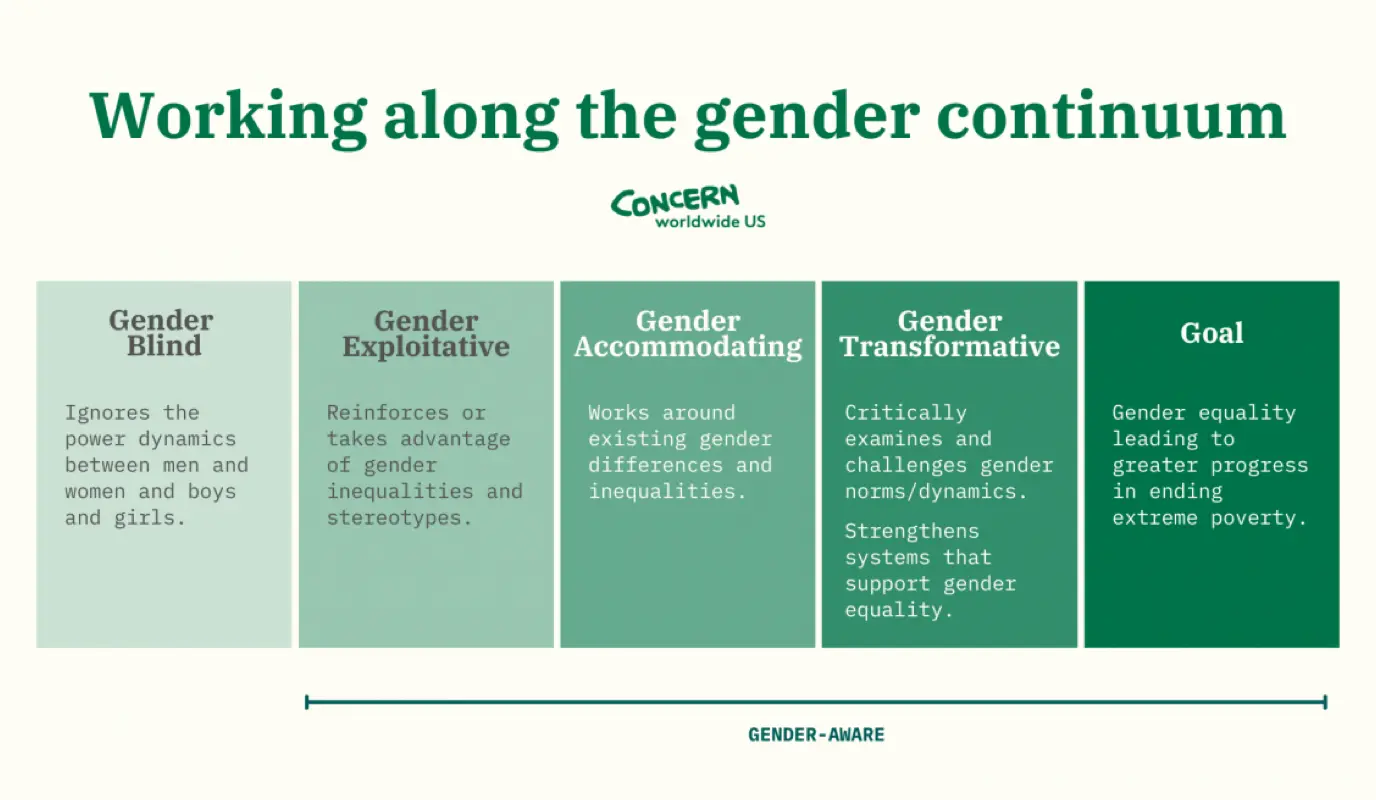

All of Concern’s programming, from health and nutrition to emergency response, happens through a gender transformative lens. That means we don’t simply work around existing gender differences or inequalities. Instead, we critically examine and challenge gender norms and dynamics in order to build equity and make greater, more sustainable progress towards ending extreme poverty. Where it makes sense, we also build and strengthen systems to support that level of equality.

Harmful gender stereotypes and norms are learned behaviors that, with the right approach, can be unlearned. When we brought the Graduation program to Malawi in 2017, we focused on working with women as the main program participants, but also designed a 12-month curriculum of monthly sessions for women and their husbands or partners called Umodzi (which means “united” in Chichewa). The sessions focused on getting couples to discuss topics such as gender norms, power, decision-making, budgeting, violence, positive parenting, and healthy relationships. By the end of Year 1, couples participating in Umodzi saw an average 10% increase in women participating in major decision-making.