How do the complex weather patterns of El Niño and La Niña actually work? Why are they so destructive? And why do they matter to humanitarian work? We break it down in this explainer.

El Niño and La Niña are a global climate phenomenon caused by cyclical shifts in the water temperature of the Pacific Ocean. While focused on a small section of the Pacific near the Equator, these shifts have global ramifications. They influence both temperature and rainfall.

Each El Niño or La Niña event lasts between 9 and 12 months, and, on average, occurs every 2 to 7 years.

What is El Niño?

El Niño is the warming phase of water temperatures around the Pacific Equator.

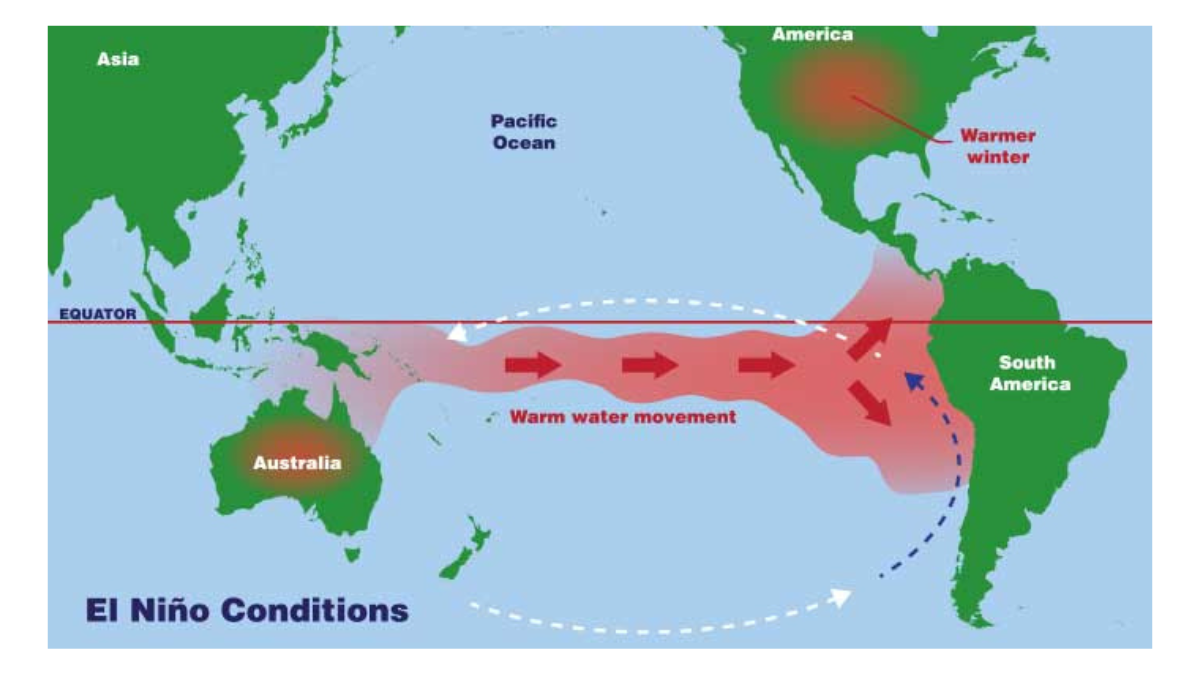

During normal weather patterns around the Equator, trade winds carry warm water from the tropical areas of the Pacific Ocean. Moving west, the winds distribute warm water from the Eastern Pacific into the cooler areas of the ocean.

During El Niño, those winds weaken, and the east-west travel of warm water stops. The winds reverse and carry warm water back east, which makes the warm part of the Pacific Ocean even warmer. Sea surface temperatures can increase by 1–3° Fahrenheit for months, or even years.

What is La Niña?

La Niña is the opposite of El Niño: an intensification of normal weather patterns. This causes ocean surface temperatures to cool down as winds strengthen and blow warm water towards the west.

La Niña events may, but don’t always follow an El Niño event.

What are the effects of El Niño and La Niña?

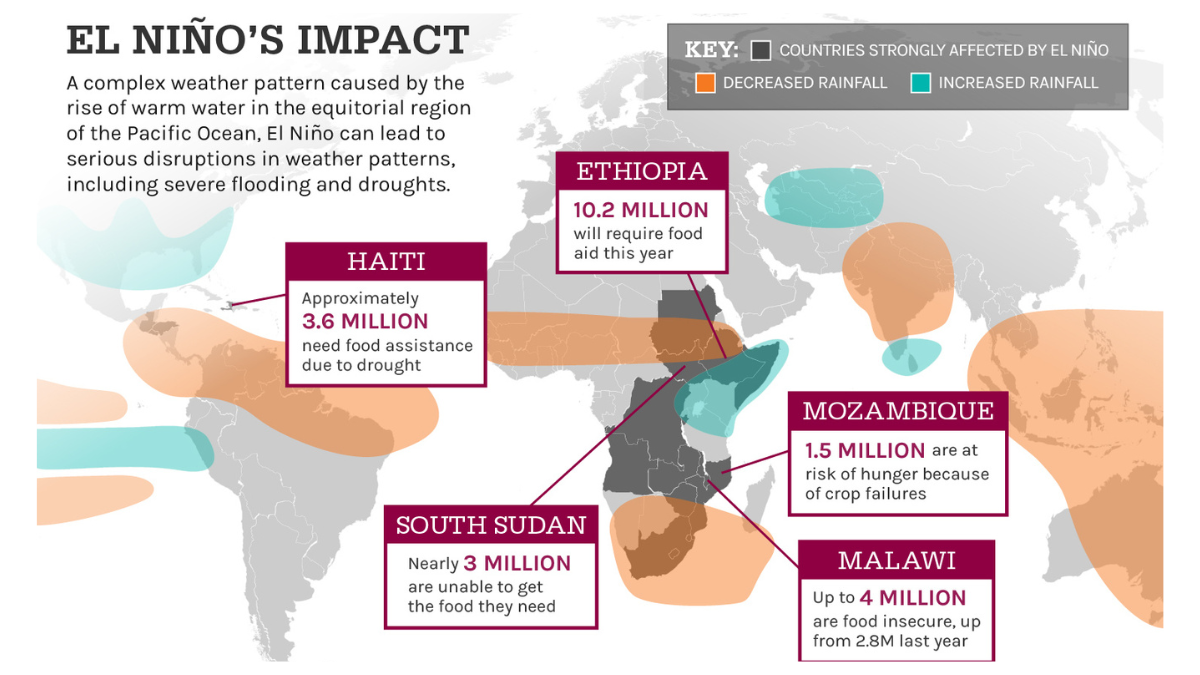

El Niño and La Niña affect not only ocean temperatures, but also how much it rains on land. Depending on which cycle occurs (and when), this can mean either droughts or flooding.

Typically, El Niño and its warm waters are associated with drought, while La Niña is linked to increased flooding. But, because the global weather system is very complex, this isn't always the case. For example, in 2015, El Niño has caused both flooding and droughts in different places.

Why does this matter for a humanitarian organization?

El Niño and La Niña have the greatest impact on countries around the equator. This includes Central and South America, the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, and eastern and southern Africa. In other words, they hit some of the world’s poorest regions the hardest. What’s more, these regions rely heavily on agriculture. Too little rain (drought) or too much rain (flooding) can be devastating for crops. A single drought or flood can mean that families run out of food within weeks.

In areas like the Sahel or the Horn of Africa, communities are already working challenging land. The Sahel, which includes Niger and Chad, sits between the Sahara desert and the Sudanian Savanna. The Horn of Africa, while close to the Equator, is mostly arid as the monsoon winds lose their moisture by the time they reach countries like Ethiopia and Somalia.

El Niño in Ethiopia

An El Niño-induced drought worsened the food security situation in Ethiopia between 2015 and 2017, leading to reduced harvests and loss of livestock. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs labeled the 2015-16 El Niño one of the three strongest episodes on record, with lasting impact on 60 million people around the world. 9.7 million of those people were Ethiopian, and lived through the country’s worst drought in 50 years.

El Niño in Malawi

This same El Niño cycle stretched across Africa, leaving 6.7 million people in Malawi food-insecure due to drought. Earlier in 2019, the country was then hit with floods as part of Cyclone Idai, causing crop failures and washing away precious topsoil. This illustrates both how these climate events can become climate disasters, and how the toll these disasters take are predominantly on the world’s most vulnerable populations. Climate change will only make the situation worse, increasing both the frequency and severity of these disasters.

Wait, does climate change cause El Niño?

No. El Niño and La Niña are natural occurrences and not caused by climate change. However, climate scientists are studying how climate change might intensify the effects of El Niño and La Niña.

Currently, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), it's unclear how the El Niño cycle may change as the world's temperature increases. “There is evidence for all sorts of outcomes,” they wrote in 2018. “Whether it is more El Niños, stronger overall events, or even a decrease in the number of El Niños or La Niñas. This uncertainty is because of the complicated give-and-take between the atmosphere and ocean with a lot of different tuning knobs that each get adjusted by climate change.”

Ultimately, the cause is irrelevant against the impact.

El Niño and La Niña: Concern’s response

Concern is providing El Niño-related support in 10 countries in southern and eastern Africa, particularly Ethiopia and Malawi, which are under the biggest strain. We also recognize that we need fundamental changes to the world’s development and humanitarian systems. There is an increasing consensus around the need to shift from responding to disasters to addressing the risk of disasters before they happen, focusing not only on emergency response but also on the root causes of disasters and extreme poverty.